Gestalt Principles of Design

A Crash Course on the Whole

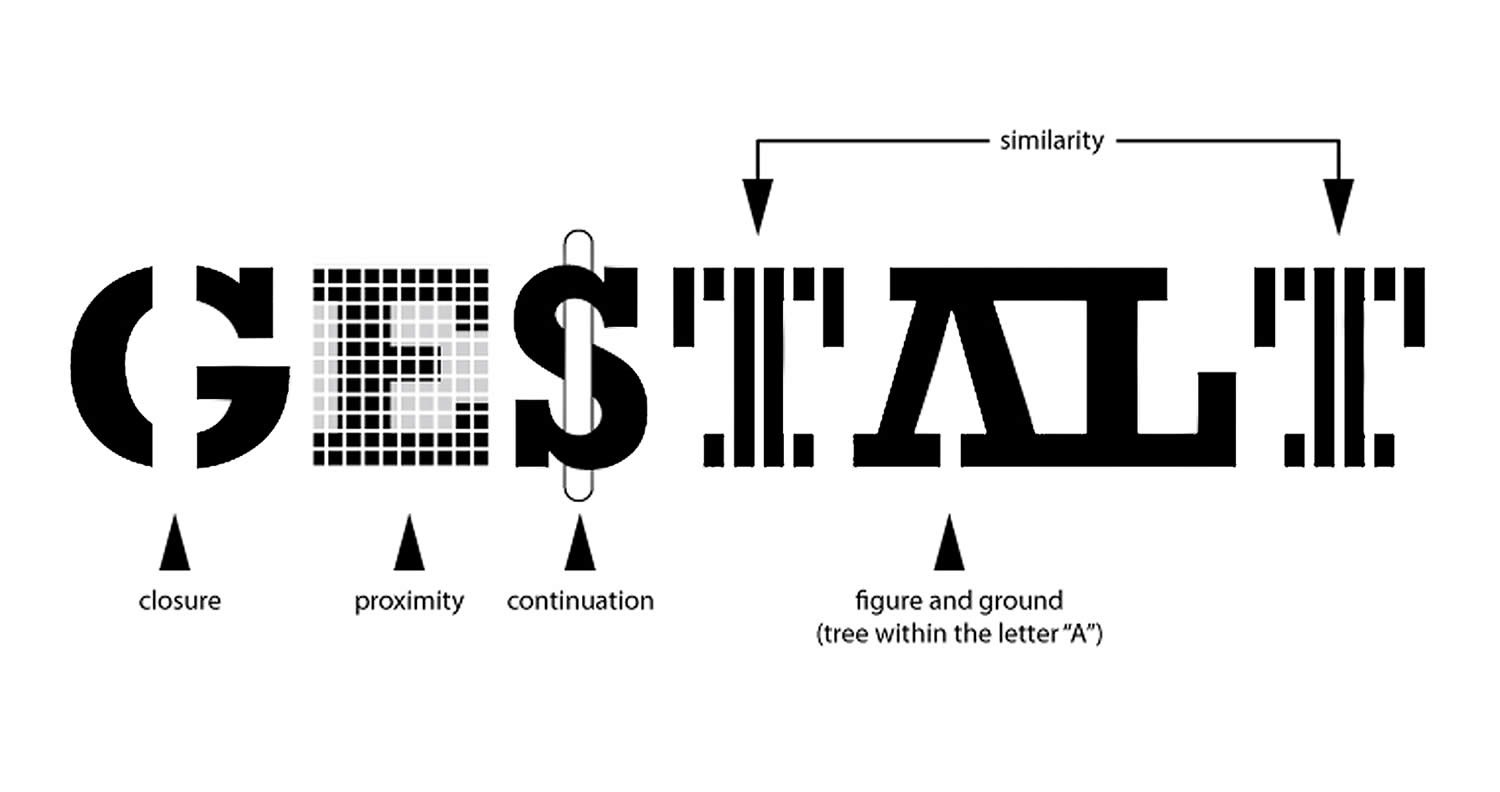

Today we're looking at 'die Gestalt', the result of early 20th century studies in psychology that described how humans perceive the world, and how it can help us make outstanding user interfaces.

Gestalt Psychology

Gestalt (ɡəˈʃtælt) feminine noun: 1. An organized whole that is perceived as more than the sum of its parts.

Around the turn of the century, German and Austrian psychologists were investigating the human mind's ability to perceive the world around it. Even though we're confronted with a world filled with exceptions and strange sights, we can somehow sort it all out. How do we come to form a meaningful, consistent perception of reality based on the chaotic conditions around us?

The prevailing conclusion of this school of psychology is that when perceiving the world, the mind sees eine Gestalt — or a "global whole" — instead of a collection of individual parts. The mind also has the ability to organize these wholes into even larger wholes. For instance, the mind can recognize a hat or a person as a whole object instead of a collection of lines and curves, but our mind can also perceive a larger whole of a person wearing a hat instead of seeing two smaller unrelated objects near each other. According to one of the founders of Gestalt psychology, Kurt Koffka,

The whole is something else than the sum of its parts.

This is how they believed we derive meaning from the chaotic world.

Seven Design Principles

Right away, we can see that the principles of Gestalt psychology are applicable to how we design user interfaces. If we can design our UI's with different levels of the whole picture in mind, we can give users an intuitive way to understand the interface. Ideally, most people wouldn't even have to know or think about how to take an action in our application. They could subconsciously predict how to do that action without prior knowledge based on these principles. Let's take a look at each of these seven principles in turn.

Similarity

The principle of similarity is our mind's bias for associating things that are alike. What this means in practice is that things with the same color, shape, size etc. are going to be perceived as belonging together. We can use this in both a positive and negative form to convey meaning. For instance, we can put a buttons all over our app that are shaped the same. The similar shape will inform the user that buttons behave consistently no matter the context they're seen in. Complementarily, if one button is green and another red, the user will stop to think about what the difference implies. Does the red button perform a different type of action than the green one?

Continuation

The principle of continuation is the tendency of our eyes to follow the smoothest path when viewing lines. We can apply this to our UI designs by using lines and borders to both separate and guide users' eyes to a certain spot. We can also imagine invisible lines connecting different components in the app. If it's possible for someone to scan across the screen with a fluid motion of the eyes and see everything, they will be able to understand the system quicker and more intuitively than if their eyes have to dart back and forth across components. Another facet of this principle is that we prefer smooth lines over sharp lines in an aesthetic sense. Adding border radii to most components will convey a softer and smoother tone than using right angles.

Closure

The principle of closure is how our brain will fill in missing parts of shapes for us. One powerful way to use this is to imply the continuation of content that's off the screen. It's common to see this in many apps nowadays with horizontal scroll sections. In these apps, the viewable section of the content will include enough space for multiple complete sections and then additional space that has one section cut off. This informs the user that the section scrolls and there's more to see. It also informs them when they arrive at the end of the scroll section because the fractional part of the content will switch sides and the part that's cut off will be "back" towards the initial scroll location.

Proximity

The principle of proximity is about spatial relationships. Our minds will group things that are near to each other and assume they belong together. Likewise, things that are far apart are subconsciously assumed to be different. One important example of this principle is the layout of user input forms. Labels, fields, and other things like helptext should be close together for a single data point and form a single input group. The space between input groups should be larger than any gaps within the groups to signify that they're separate entities at a higher grouping level. This principle can be combined with the similarity principle to great effect. Buttons at the bottom of a form can be grouped together with the form and with each other to show that they apply actions to the form. The negative version of the similarity principle can then be applied to the buttons to show that the buttons do different things.

Figure / Ground

The principle of a figure and ground relationship is similar to closure but focuses on how our brains will subconsciously select a foreground and background based on shapes, colors, and perceived depth. Using different shadows adds depth to our interfaces. Lighter, brighter items with bigger shadows appear to be close to us and stand out as important. Components with darker muted tones lacking strong shadows appear to be in the background or underneath other things.

Symmetry (Order)

The principle of symmetry and order is about the brain's ability to perceive things in a simple and recognizable way. Overlapping shapes are not perceived as a new unexperienced shape, but overlapping simple shapes. One way we might apply this principle is to create natural visual representations that indicate more information. For example, imagine a stack of cards that are slightly fanned out so just a small piece of each card's side can be seen. We can see the card that's on top of the stack and know that the stack itself contains cards that are of a similar kind.

Common Fate

The principle of common fate concerns results of actions and particularly motion or perceived motion. Things that are moving in the same direction will have a common fate, but also, actions that are performed in a similar way will have a common fate. This is a vital element for a simple, natural user interface. If I delete something one way in one part of the app, it should be similar in another. Everything from the actual user input down to the styling of the buttons and visual feedback should indicate that this interaction will result in the same fate that it did elsewhere. This can be particularly powerful for touch screen apps where gestures perform actions. Each gesture should not only be internally consistent within your app, but can also draw on the powerful, shared, experiential context that we've all accumulated interacting with other apps. Be sure to consider this if you buck the trend in your apps.

We see that people build up their understanding of their environment using these principles. If we can build our UI's to follow them, we can leverage our users' previous life experiences to make their interaction with our system frictionless. There's so much more to dive into on these principles that I could never do the whole field justice.

This topic has been a great example of how all kinds of research can inform our development decisions and I highly recommend looking into this and other psychological research if you really want to level up your design and user experience game. Bringing in expertise from different fields and disciplines can give us that interesting view point or spark our creativity to make our products better. If you're interested in a good, in-depth look at the amazing benefits of interdisciplinary study, I'd highly recommend checking out Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World — which might be one of my top 10 favorite books of all time — and my post on some other recent reading I've been enjoying.